Sometimes I travel to see the world; sometimes the world comes to me. Of late, I regularly have been providing some of the medical care at the largest refugee reception center in Tucson. These “centers” are for families, usually with young children, released by ICE. We feed them, screen them for maladies that might affect them during their subsequent travel, house them for one to three nights, provide them with additional clothes they may need, and arrange for their bus or air travel to their sponsor — usually family — elsewhere in the U.S.

While the center has bounced around for the past several months, for at least the next six months we’ll be working from the ornate, wood-paneled former Benedictine Monastery on Country Club Road. Catholic Community Services provides the backbone support, but all of Tucson’s religious communities have contributed. Quite a few UA physicians, residents, and medical students have been participating regularly.

To get a picture of our population, imagine walking into the wide, sedate, tiled hallway and seeing several young boys, who look and act no different than our neighbors’ children, howling with joy as they kick a soccer ball around. In a side room, volunteers patiently work with a volunteer language professor in Michigan, who translates via speakerphone the vital information needed to process a Russian family. We’ve had Africans and Mexicans come through, but most of the folks now are from Guatemala and Honduras. While most people (up to 60 a day) speak Spanish, many are more comfortable in one of the many indigenous languages. What we tell the parents is that within a couple of months, their children will be speaking fluent English; probably not true for most of the adults.

Medically, we screen the patients, provide basic care, administer the influenza vaccine supplied by the county health department, and refer out those who need anything more. Aside from viral illnesses, pediatric diarrhea, and mild dehydration (some arrivals haven’t eaten anything in four days), we’ve identified a child with untreated grand mal epilepsy (no medication since leaving Guatemala), a child with possible tuberculosis, a pregnant child who had been raped before leaving for the U.S., and children with pneumonias.

If you’re wondering whether more volunteers are needed (medical and non-medical), the answer is yes. Send me a note (kvi@email.arizona.edu) and I’ll pass it on so you get on the email notification list. You don’t have to speak Spanish, although it helps.

Semi-international experiences also occur with my work, including now being on the board of directors of the long-running (15 years) Clínica Amistad in the El Pueblo Regional Center next to Congressman Raúl Grijalva’s office. Staffed by volunteer medical professionals, students, and others, the center serves the medically indigent. Clinic medical care, labs, and imaging are free to the mostly Spanish speaking patients, and the clinic pays the costs for additional medical services other than surgery and when they must be sent to outside specialists. The clinic’s greatest need is additional funds, since that is what they rely on to pay for rent, supplies, labs, and other medical services. If you’re interested in donating (money, not supplies), you can send it to P. O. Box 27284, Tucson, AZ 85726, or email it to Nicole Glasner, executive director for development, at exec@clinicaamistad.org. The clinic is a registered 501(c)(3) charitable organization.

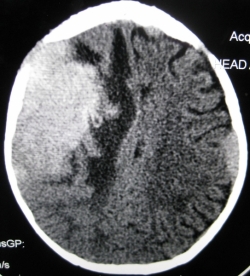

Of course, since the last newsletter, I’ve been back to Guyana, with my next trip scheduled in May. Aside from the numerous cases of neonatal sepsis (generally flown in from Guyana’s “interior” in the Amazon jungle), cerebral malaria, leptospirosis, dengue, and MVCs, some interesting and unfortunate cases stood out. These included identifying a large extended family with tuberous sclerosis that we investigated because of a suspicion and a child with abnormal seizures. Guyana’s public health service is now involved and will assist them. We also identified a patient with Von Recklinghausen’s Disease. Although she was too old for genetic counseling, that was not true for the rest of her family. Stab wounds are common everywhere, but this patient’s mechanism was unique, at least in our hemisphere. His assailant stabbed him several times with a stingray stinger used as a knife. Only a minimal pneumothorax resulted.

More tragic was the four-year-old girl with known neuroblastoma who our EM resident found had a small skull defect. She suspected it was the tumor and, unfortunately, was correct. Last was a tragedy that we see about once a week. Usually an adolescent (usually a girl) swallows one “carbon tablet,” a pesticide, because of a spat with the parent, a boyfriend, or a teacher. They arrive in the ED walking, talking, and not usually feeling much other than nausea. No matter what the treatment, this small dose of aluminum phosphide destroys the body and they die within hours. The child I saw on my last day there this trip, who presented only minutes after ingestion, had the maximum currently recommended treatment, but died 12 hours later. There are public health restrictions on selling the product, but you can still easily purchase it.

Global medicine — whether in Tucson or internationally — is a varied and interesting practice. The downside is that you also see the world’s dark underbelly.

*All identifiable patients gave permission to be photographed.

Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA, FACEP, FAAEM, FIFEM

Professor Emeritus, Department of Emergency Medicine